コメンタリー

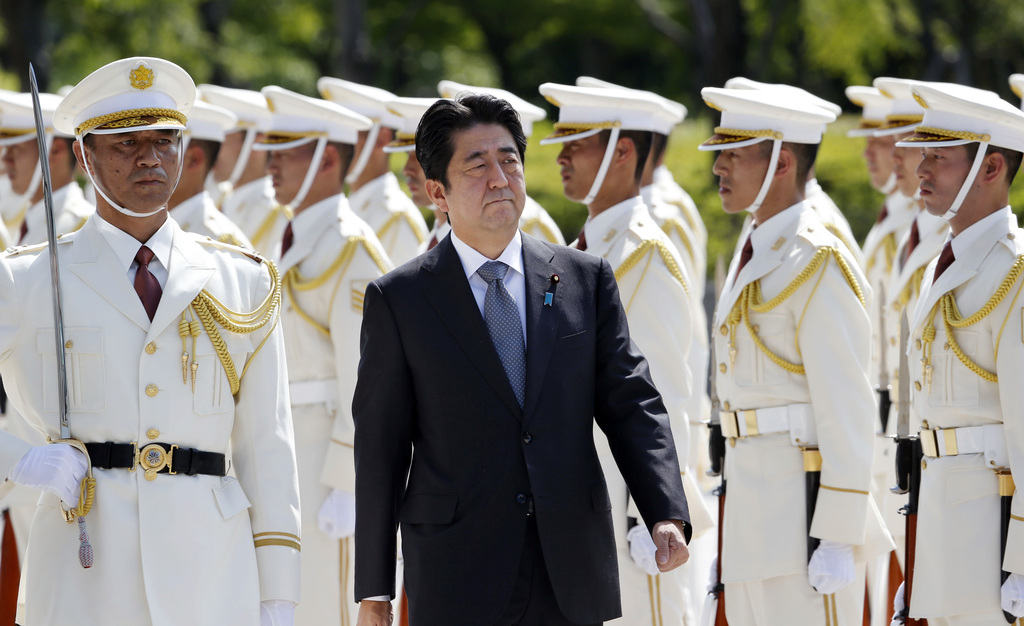

ROLES INSIGHTS No.2022-04: "What Abe's Death Means for Japanese Politics: Japan has Lost a Compass and a Driving Force" by Guibourg Delamotte

Abe Shinzo’s political debut as prime minister, in 2006, was uninspiring. He resigned within a year and the health explanation provided seemed flimsy at the time. His mentor and predecessor as prime minister Koizumi Junichiro himself expressed disappointment. Yet Abe had already laid the foundation stones of a far more substantial legacy on which he was to build in 2012 when he regained power.

Japan has had few strong figures with vision for their country. Abe changed not only the way Japan was perceived on the world stage, but also Japan's vision of the world. During Abe's near-decade in power, her international influence bloomed. As early as 2007, he drew attention to the geopolitical coherence of the Indo-Pacific region. In 2016 under his leadership Japan’s “vision for the Indo-Pacific” alerted the international community to the region’s strategic importance and China’s increasing presence there. The US, France, Britain, the EU...soon followed with Indo-Pacific strategies of their own. Japan’s conception of regional international security was founded on ‘soft’ development assistance to emerging countries through better connectivity and ‘quality’ infrastructure, and also assumed a ‘harder’ direction, on maritime security and Freedom of navigation.

Abe also opened up the possibility for industrial cooperation and the joint development of weapons systems with partners other than the US. He developed defence dialogues with neighbouring Asian states. With South Korea, he endeavoured to defuse lingering historical issues and agreed to (again) compensate ‘comfort women’. He deepened friendships with Australia and the US by commemorating their war deaths and prisoners-of-war and visiting Pearl Harbour. Abe stabilised relations with China, after tensions under Koizumi and the Democratic party's years in power from 2009 to 2012, even though Chinese incursions into Japanese waters increased (after a reduction in numbers in 2018).

Abe gave the country a strategic vision by establishing a National Security Council which brings the Defence, Police, and Foreign Policy establishments together. The Law on the protection of sensitive information enabled greater intelligence cooperation with the US (which the 1997 Japan-US bilateral Security guidelines had called for). Abe also undertook a vast reform of Japan’s international cooperation and defence legal system in 2015. Japan had relied on ad-hoc laws until then, most of which dealt with specific circumstances with which they expired, nonetheless establishing precedent for the next set of measures. That way of dealing with international crises was unpredictable for Japan’s international allies as each crisis brought parliamentary debates and no one could foretell if and how Japan would take part in an international coalition. Furthermore, from 1992 when the first international cooperation-related law was adopted, citizens elected a majority party whose head, as prime minister, then made decisions for which he held no national mandate, as indeed citizens had elected him before the crisis and ensuing law. Worse yet, citizens might elect a premier minister while disapproving his stance on deployments because foreign policy and deployments seemed a distant or secondary issue (Koizumi was re-elected in 2005 in spite of the people’s opposition to a deployment to Iraq). The vast 2015 reform solved those issues by characterising different crisis situations and pre-establishing corresponding legal frameworks, thereby laying out the government’s options in terms of Self-Defence Forces missions.

Abe (with the Cabinet Legislation Bureau whose head he had changed) established that Japan could use collective self-defence if an ally was attacked and Japan’s survival or the lives and freedoms of its people were thereby at risk. Japan can now provide logistic support (excluding weapons) in crisis situations which bear an important impact on Japan’s security. Furthermore, Japan can now cooperate with international organisations other than the UN on peace-keeping or humanitarian missions, and undertake peace-making activities (the monitoring of a ceasefire agreement for example). Importantly from the point of view of democratic control, in each instance, the government must seek parliamentary approval. This new framework enabled Japan to be more effective within the boundaries of an unrevised Article 9.

Retaining power came at a cost. The opposition did not take kindly to Abe. Much of Japan’s parliamentary rules rely on precedent and negotiation with the opposition, from when parliament sits, to the order of passage of bills. Abe rode roughshod over convention and instead asserted majority-rule disregarding the opposition’s opinion on bills. Dissolving the Lower house in 2014 and again in 2017 before the end of the legislature, at times which suited the opposition little, he maximized his presence in power by coaxing his party into giving him three three-year mandates as leader. Thus, he retained power for 8 years, thereby becoming the longest-serving Prime minister in Japanese history. He asserted his control of civil servants through a 2014 law, which increases the Prime Minister’s nomination powers – breaking with the tradition of neutrality of the civil service. Political scandals in 2017 and 2018 demonstrated favouritism and use of public funds for the benefit of some of his support groups.

Notwithstanding what Machiavelli might have advocated as necessary to the skilful exercise of power, Abe had become a monument of Japanese politics, one of those heavyweights whose influence endures even after leaving power.

Even though Abe had resigned his post as Prime minister in 2020, his counsel was listened to and set the pace. At the end of February 2022, he recommended that Japan discuss nuclear deterrence with the US and nuclear-sharing, and in June, when President Biden visited South Korea and Japan, the redeployment to South Korea of strategic assets, possibly tactical nuclear weapons, and close cabinet consultations with Japan, were agreed upon. How is Japanese policy developing now that he has left the stage?

Current PM Kishida follows in Abe's footsteps, sealing international partnerships with partners and allies, and increasing naval deployments in the Indo-Pacific. Japan has signalled a willingness to partake in future AUKUS technological contracts – industrial cooperation with allies was made possible when Abe relaxed rules on arms exports, which are now allowed if they will contribute to international peace or to Japan’s security and not reach a country at war or be in violation of international law (exports to third parties require the GoJ’s approval). Kishida has highlighted “economic security”, the importance of which Abe, who had established an economic security unit in the National Security Council and pushed for a reform of the legal framework of foreign direct investment in Japan, had been fully aware.

There are elements of departure from the Abe line too. Abe succeeded in establishing friendly relations with all of the world’s leaders. No other country in the world has simultaneously cordial relations with Arab countries, Israel, and Iran. Who else managed Donald Trump better than Abe? He made friends with him while bringing to life the Comprehensive Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership after Trump announced the US would no longer be a member of the TPP. Abe also negotiated a bilateral free trade agreement which would not be disadvantageous to Japan, and held off discussions on the level of Japan’s Host Nation contribution (Japan’s financial contribution to the costs of US bases in Japan), when Trump wanted it increased. There was even some benefit to an American president taking on China and making overtures, albeit without prior-ally consultation, to North Korea (though Japan was sceptical as to their outcome).

The war in Ukraine has forced Kishida to side with the G7 in adopting sanctions against Russia – Kishida’s “realism diplomacy for a new era”. Back in 2014, when Russia invaded Crimea, Abe had withheld from adopting sanctions in the hope that Putin would return some of the lost Northern Territories.

Under Abe, defence budgets increased steadily but remained at 1% of the GNP. The ruling party has advocated their doubling and acquisition of strike capabilities in the form of Intermediate range ballistic missiles, in view of North Korea and China’s improving capabilities which make Japan’s missile defence system insufficient. Though the rationale remains defensive, Japan’s acquisition of first-strike capability will mark the end of its “defensive defence policy”, the Yoshida doctrine, which Abe for all his reforms in the field of defence, had stuck to.

On the domestic front, the Abe faction was the strongest in the LDP. It is now left leaderless. Whether or not his faction will remain as strong and consistent in its support of the government without the pull of a charismatic leader remains to be seen, so too whether or not Kishida will know how to navigate the political scene so as to become the compass Abe has been.

***********************************************

Guibourg Delamotte is a Senior Lecturer in Political Science and Japanese studies at France’s Inalco; Visiting Associate Professor at the Tokyo College; Visiting Fellow at RCAST; Visiting Associate Professor at GraSPP, the University of Tokyo.

同じカテゴリの刊行物

コメンタリー

2026.02.19 (木)

コメンタリー

2026.02.18 (水)

コメンタリー

2026.01.27 (火)