On November 8, over 370 full and alternate members of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) gathered in Beijing for the four-day sixth plenum. The closed-door plenums are significant part of the Chinese political calendar, often serving as precursors to new laws, plans, and policies. Specifically, the sixth plenum has gained much attention given that the 20th National Party Congress is scheduled next year.

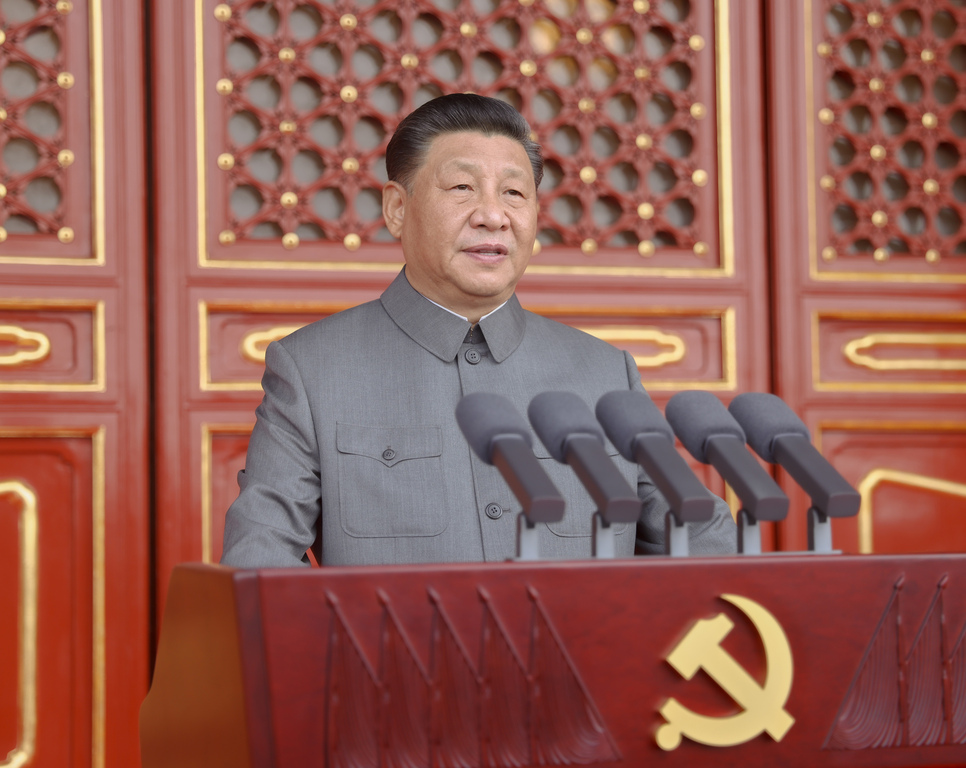

The highlight of the sixth plenum was the adoption of the so-called “historical resolution” that purports to define the community party’s (and essentially the nation’s) historical identity while also cementing the leadership. The resolution has only been adopted twice before, with the first in 1945 under Mao Zedong and the second in 1981 under Deng Xiaoping. Adopting the “historical resolution” helps to set the leadership-based historical narrative, where Mao is depicted as the founder of communist China, Deng as the guider to modernization, and Xi as the one that makes the nation an unrivaled power. The resolution itself came as little surprise, as it only further confirmed the developments of the past nine or so years to bolster Xi’s power.

The issuance of the “historical resolution” fits perfectly with the CCP’s centenary celebration held in July this year. But the CCP’s obsessive attention to history is not simply about glorifying the authoritarian regime’s past. Rather, much of the new resolution is future-oriented, indicating how the CCP perceives the present as the turning point, calling on new strategies and measures to achieve the nation’s “two centennial goals” of becoming a “moderately prosperous society” by 2021 and a “fully developed, rich, and powerful” nation by 2049. While there are debates about whether or how China achieves those goals (especially the second), the point is that Xi Jinping is set as the one that leads the nation in that direction.

How Xi exercises his long-term leadership much depends on his (and the party’s) policies, but also the extent to which his authority is systemized. Although it is hard to be definitive, Xi’s leadership has been and will continue to be distinct from those of Mao and Deng. After all, China’s economic, social, and geopolitical circumstances are much different, and the nation’s status has also changed significantly from the years when Mao and Deng led the communist giant.

The developments that have taken place under Xi’s watch are notable. Economically, the Chinese economy has not only continued to grow with major industrial transformations but has also worked to create its sphere of influence through the Belt and Road Initiative. Militarily, the People’s Liberation Army continues to modernize at break-neck speed, not only in conventional platforms but also in strategic weapons systems, as well as cyber and electronic warfare capabilities. Moreover, there have also been major structural reforms to the maritime law enforcement organs, allowing China to flex its muscles in seas – particularly under the new Maritime Traffic Safety Law that came into effect this September. While the capacity for further developments is certainly not infinite, China views the developments to date as merely the initial stages of their long-term plans.

The fate of China under the Xi era is anyone’s guess. Yet for the foreseeable future, greater political stability under Xi will lead to greater confidence and willingness for China to demonstrate its power, raising new concerns in the international security context. While the threats posed by China are certainly not new, it is time for the states in the Indo-Pacific, including the United States and other like-minded states to recalibrate their strategies for the new challenges and uncertainties.

***********************************************

Ryo Hinata-Yamaguchi is a Project Assistant Professor at the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology at the University of Tokyo and an Adjunct Fellow at the Pacific Forum. Ryo can be followed on Twitter at @tigerrhy.

Related Publications

Commentary

2025.03.30 (Sun.)

Commentary

2025.02.26 (Wed.)

Commentary

2024.09.18 (Wed.)

Commentary

2024.09.01 (Sun.)